My review of Flow by Robin Scofield at Red Fez

My Red Gez review of Lantern Lit Vol. 4

“In the fourth volume of its Lantern Lit series, Dog On A Chain Press presents three chapbooks, poetry collections by William Graham, Mat Gould, and Sheldon Lee Compton. Publisher Beasley Barrenton describes the poets’ combined work as ‘the gospel of real life shit. . . .’ All three poets, according to Barrenton, ‘live and breathe the same incandescent air,’ as he does himself, ‘whether at the edge or deep within The Blue Ridge Mountains in the heart of Appalachia.'”

Read more at Red Fez.

Red Fez review of The Tongue Has Its Secrets

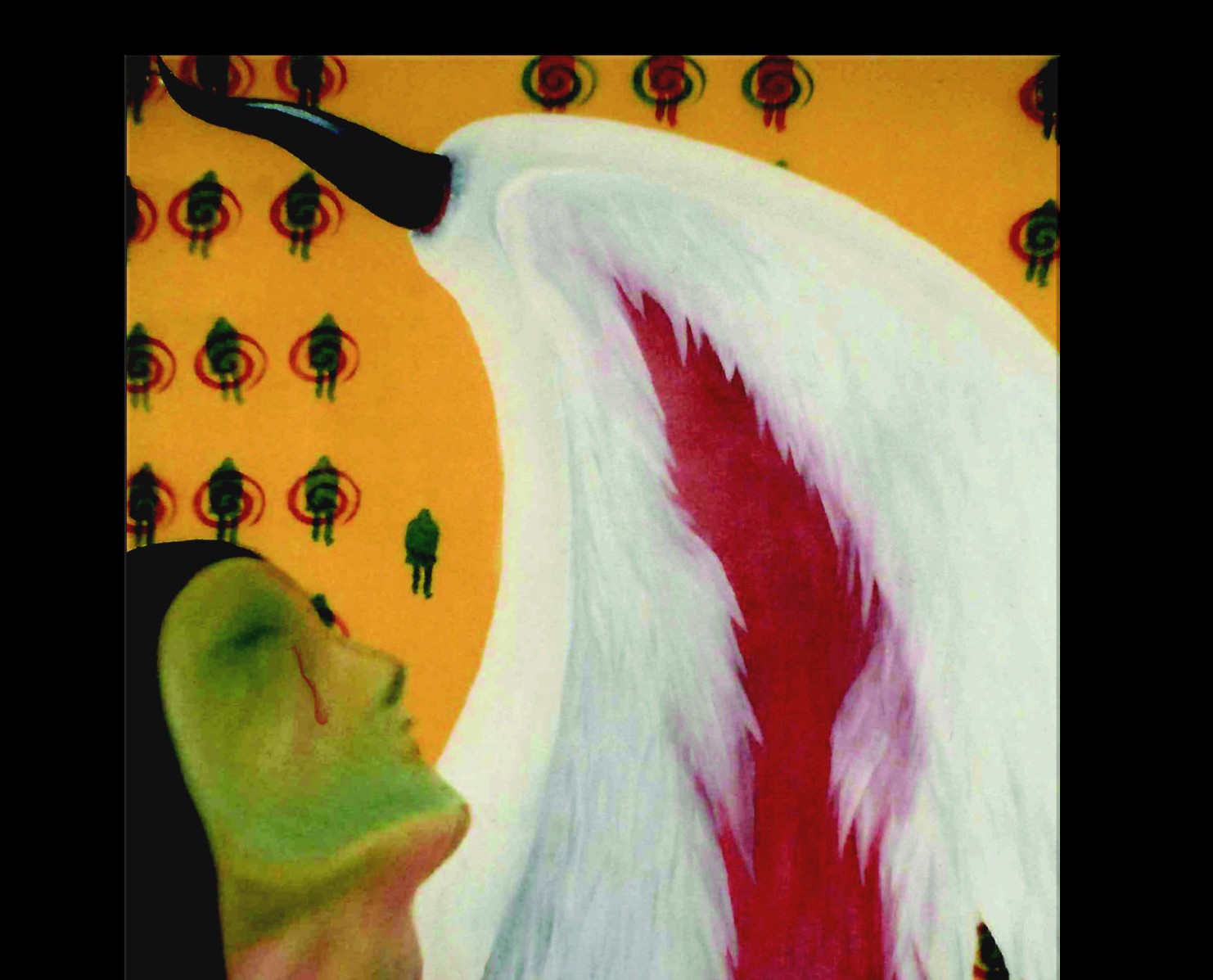

Perhaps a Southwestern state of mind is a prerequisite for a full appreciation of the Sandia Mountains and Chaco Canyon landscapes that populate Donna Snyder’s latest collection of poems, The Tongue Has Its Secrets. Yet a stranger to these parts can approximate a high-desert way of knowing, in the same way that a male reader may discern, if only as a tourist, the invocation of ghosts from a woman’s way of seeing, the subject at the heart of Snyder’s latest work.

Dea tacita

Lara’s tongue severed by the sky for indiscretion

Love led her on a spiral path deep into the laurel

She gave birth to little gods but was forever silent

She lingers at cross roads

Tends the dead

What is evident from the first poems is that Snyder avoids the fear of modern vernacular that seems to occupy many poets who visit natural sites, hoping to evoke ancient gods. We could all be judicious with our language while trying for the perfect Mary Oliver setting, but any ancient god worth a prayer won’t mind the occasional reference to a pop song or video game. Snyder’s language is at once formal and casual, giving works like ‘Prepare to Ululate’ surprising depth.

Blue norther’

In the North Texas Panhandle, southbound truckers

blast down Hwy 83, headed to where the wind’s not

from the north and not called blue.

Winds and storm outside become Valkyries,

the concrete septic tank a magic stone. Women

warriors ride like furies across the frozen plain.

An Irish woman outruns a chariot,

gives birth to twins,

lays a curse.

The wind takes my spirit in its arms and flees.

Mama lights the candle, locks the door.

There are plenty of two-lane highway odes in this world paying homage to modern gods of transport, and plenty of chants that attempt to revive Anasazi imagery, but Snyder is rare in being able to meld the two. Poems such as ‘Blue Norther’ and ‘My Heart Makes Chorus with the Coyotes’ successfully bring the two worlds together with an impressive degree of success.

Snyder obviously takes the most time with the multi-stanza works spanning two or three pages that attempt to disentangle layers of spirituality. Sometimes, the longer poems are not as effective as the shorter, more direct works. ‘Bear Who Loves a Woman’ is an obvious exception to this rule, a complex and interwoven longer work that is one of the book’s highlights.

The collection ends with the tight and disciplined ‘Supplication,’ which seeks to call upon the right panoply of gods without a wasted syllable. Many of Snyder’s fans may find the poem a perfect summation and distillation of the entire collection. But even those of us more secularly grounded in cynicism will find the pair of poems near the book’s end, ‘The Truth of Vikings’ and ‘Aqua de mi sierra madreTM ‘ to provide just the right mix of breathless voice and raised eyebrow. In short, there’s a brand of salvation in The Tongue Has Its Secrets appropriate for just about any seeker.

The truth of Vikings

The music in her head makes her scared,

as if Vikings still brandished their blades

from the decks of ships fierce as dragons.

Afloat in an ageless river,

the leaves are chill flames.

Cold rains obscure the water’s source,

hiding it away like the secret of a woman’s

aging body, rain, a woman’s sluggish heat.

She is apples and pears ripened

in her own sweet skin.

Only the moon can match

the luster of her opalescent belly.

Her mouth makes shadows. Her hair

a burning bush.

Her fingers a doorway,

iconic as a religious artifact. She is on route

to the end of being on the back of a red swan,

on the way to nothingness made tolerable

by ritual and fire.

Through the wind, she hears the shriek

of disconsolate women who no longer

believe love will save them from sorrow.

There is no home now, they wail.

There is no safe place.

Death tastes like winter flowers.

She knows this because she knows

things she is not supposed to know.

She stands so close she can hear

warriors tell each other secrets.

The truth is that neither love nor death

diminishes you. The way to truth

is a life suffered, a drunken waltz.

She stands so close her howl is lost

in the roar of music inside her head.

She is wordless before the fact of Vikings,

truth found in a harsh yellow light.

https://www.redfez.net/nonfiction/610

Susan Hawthorne is a polymath – linguist, poet, script writer, aerialist, ecologist, publisher, and scholar. She has worked in a circus, as a professor, as an editor for Penguin Books, and as a publisher with her own independent press. She is fluent in English, Latin, Ancient Greek, Sanskrit, and conversational Italian in various dialects, as well as the history and art of each of those cultures. She also possesses at least a working knowledge in languages such as Linear A, proto-Indo-European, French, and the Angelic tongues, and is quite capable of making use of Old English, Etruscan, Kartelian, Akkadian, Vedic, Prankrit, Sardinian and other languages.

Hawthorne peppers her poems with references to calculus and physics, demonstrating yet two more arcane languages with which she is conversant. She has published on biodiversity and erotica, and has books of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction. This diverse expertise and learnedness provide the vocabulary and content of Hawthorne’s poetry, which is no less than an attempt to rescue and resuscitate Woman in all her power and glory, to restore the lost culture of women ignored or obliterated by previous scholars. In Lupa and Lamb, Hawthorne ably incorporates almost all areas of her skills and knowledge, except, perhaps, her work as an aerialist.

A book of poems, scripts, fragmentary artifacts, myth, and myth-making, Lupa and Lamb has characters which blend together through time and “fold in and out of one another’s stories,” from pre-historic archetypes to contemporary travelers in Rome, as described in the Main characters page that precedes the body of the book itself. Two characters go by multiple names and represent various female personae throughout time. As described in the poem “nuraghe,” these two characters

. . . walk hand in hand

between the lines . . . tread winding paths . . .

spiraling through intangible space.

Indeed, the book itself proceeds in a spiral, moving back and forth through temporal planes, between myth and history, between fact and imagination. The first poem of the collection, “descent,” captures the liminal nature of dates and time expressed throughout the book, and mentions the recurrent theme of history and memory reconstructed and reclaimed.

I was here before

thousands of years before

your hundred mouths

shouting. . .

shouting descent into

the dark thighs of your cave

. . .my hair snake-wreathed

Etruscan Medusa

speaking with a hundred voices

the sibilant hiss of prophecy . . .

I flail at vanishing memory

bruised rise from the darkness . . . .

A third character is called Curatrix, described as the “framer of this manuscript and responsible for collecting ‘lost texts’ from ‘the present to as far back as 300,000 years.” Another character is Sulpicia, who lived in the time of Caesar Augustus and is “the only woman whose poetry has survived in Latin from Ancient Rome.” She and the Curatrix work together to re-see the remnants of her poetry, looking at it with eyes who want to see strength and beauty, a source of inspiration and comfort to contemporary women. Livia, another character, was empress of Rome by virtue of a marriage to Caesar Augustus, the mother and grandmother of later emperors, and a woman whose power in Rome was recognized throughout the Mediterranean region’s countries and cultures. In the central conceit of the collection, it is Livia who has organized a great party and invited women and goddesses from various epochs to gather at her home with the intent to create a new text from the forgotten, suppressed, fragmentary, or merely lost records of women of power.

A PhD and university professor, Hawthorne created this genre-busting and inventive collection as a tool to educate but, as the Curatrix states, “academic tedium only gets you so far.” Notwithstanding its side bar commentary, explanatory endnotes, bibliography, description of main characters, and a note on dates, Hawthorne’s creativity transcends academia and scholarship. She wields images and emotion deftly, creating a thing of grace and beauty exquisitely balanced between scholarship, cultural history, a linguist’s pyrotechnics, poetry, and theater. Come to think of it, perhaps she does make use of her background as an aerialist. But make no mistake, this book is poetry, epitomized in the poem “ancient nerves,” set forth here in its entirety.

a day of ancient argument

when with zealous ear and helpless eye

I go in search of Etruscan relics

find italic grapes oozing sweet nectar

on a frieze birds tweeze worms from soil

ewe wolf uterine maze

night’s death hour I wake

to a giant ginger object

rise and sink into oblivion

it was only the moon

sailing through cloud

breast parrot orange

on this feathered planet

or a brazen angel trumpeting dawn

Her poetry easily stands alone as poetry, irrespective of the depth of scholarship, and the exceptional quality of her writing has been repeatedly recognized by being short listed or placing for various prestigious prizes, both in Australia and the US. Her poetry has been translated into both German and Spanish. As well, she has won residencies funded by the Australian government, living, studying and writing in Rome and at the University of Madras in India.

As noted by Danica Anderson, a sociologist and international expert on healing from war crimes and other catastrophes, says that “what are remote events become social relationships threaded from the past to our life . . . [and] manifest meaning on what it means to be female.” Danica Anderson, in a December 27, 2014 conversation on Facebook labeled Blood & Honey Herstories- Charting the life. According to Anderson, we carry buried within us the memory of experiences, particularly trauma, that our ancestors encountered. Hawthorne’s book is a beautiful tool for us to access those memories. Repeated motifs include rape, incest, sacrifice, and martyrdom, demonstrating how violence against women is either suppressed, recast in euphemism, or transformed into sanctity. Hawthorne grieves the deprivation of a full life for women of patriarchal religions, as in “Hildegard,” where she describes nuns as

separate and celibate

they have dragged themselves

into exile like doves without nests.

She provides lists of goddesses who were repurposed as saints, having “dual citizenship,” she puts it.

While certainly quite serious in her aim for her collection’s cultural significance, Hawthorne’s book also makes use of puns and has recurrent erotic passages. Like so many such exchanges throughout history, sometimes a poem works on multiple levels, the sensual details hidden within the text, recognizable only to one looking for them. The poem “Diana shears Livia’s flock” sets out the steps of shearing sheep, yet the details are so sensuous it is hard to imagine that the writer intended nothing more than a description of a mundane task. Here are a few lines that underscore my interpretation.

. . . it’s a trust thing

she has to relax

fold her into your knees

with a firm but not tight grip

hold her close

begin on the soft belly

and back leg

dance your way

and step through

to neck and shoulders

so intimate a move

her head tipped sideways

Like the listing of the many goddesses in The Homeric Hymn to Demeter, Hawthorne’s poems often feature lists. She names ancient rulers and writers, goddesses from cultures around the world, and female friendships through history, drawing parallels between these heroic women and more modern or contemporary artists, writers, and activists. Her litanies create a new universe, spiraling out into the cosmos, both into the past and forward into the present, populated with the “forgotten women,” causing, as she writes in her poem “breasted,”

a vibration in the air rarely felt in these past

six thousand years.

The illustrious guests at Livia’s party permit Hawthorne to educate the reader through poetry, translations of “lost fragments” of ancient texts, while simultaneously linking lives of women that transcend the ages to heroic and creative women in today’s society.

In Lupa and Lamb, Hawthorne’s artistry spins the silken strand that connects women and their achievements throughout time.

My review of Progress on the Subject of Immensity by Leslie Ullman, published in Red Fez.

My review of John Thomas Allen’s book, Lumiere

John Thomas Allen searches for the eye of God on a trail blazed by luminaries of literature and philosophy. From Arthur Rimbaud to Andre Breton, by way of Anthony Burgess, Mário de Sá-Carneiro, Epicurus, Paul Célan, Gertrude Stein, Guillaume Apollinaire, the Virgin Mary and others, we arrive at a time and place “where the ozone of white glass glows brighter and brighter with the smoke of memory machines. . . .